State ownership and the capitalist market

When confronted with the brutal truth about Zimbabwe’s domination by the multinationals, the Zanu(PF) leaders often change their argument. Dropping their praise of the “free market”, they claim that through the state-owned sector of the economy, plus state regulation, it is possible to safeguard the interests of the masses.

Is this true? Do the state-owned industries give the government any real independence from the general operation of the capitalist economy?

Zimbabwe’s state-owned sector does not consist only of the companies brought up in recent years. As in every capitalist country — especially in the colonial world — certain important industries and services have been developed by the state because the capitalist class was either unwilling or unable to invest in them.

The railways and the steel plant at Redcliffe, for example, were state-owned even under white rule. Also in racist South Africa the state has played a key role in developing many industries and services.

Yet state ownership remains very limited and the weight of foreign capital immense.

In 1988 the Confederation of Zimbabwe Industry (CZI) published a survey which showed that just 16 per cent of industry was state-owned while 84 per cent was capitalist-owned. The Industrial Development Corporation, through which the government manages the companies which it owns, ran only 15 companies by 1988.

And many of these companies continue to be run by capitalist managers who are guided by the interests of the capitalist class.

The economy as a whole remains tightly controlled by the white capitalist elite. Despite “Africanisation”, whites still dominate the pinnacles of power. Most black managers are in junior and, sometimes, middle management levels not popular with whites — for example, as public relations or personnel officers to deal with “blacks” and workers.

The CZI survey was trying to show that the domination of foreign multinationals was something of the past. According to this survey foreign companies owned just 25 per cent of fixed assets in manufacturing industry while local capitalists owned 50 per cent.

However, this survey only counted companies as “foreign-owned” if more than 50 per cent of shares had foreign owners. It therefore excludes companies with less than 50 per cent foreign ownership.

The result is completely misleading. As we have seen, at least two-thirds of production in Zimbabwe is in the hands of foreign multinationals. The reason is that the multinationals’ power does not depend simply on the number of shares they own.

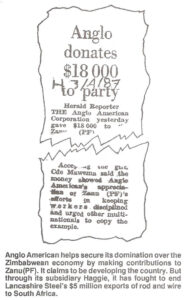

Anglo-American, for example, has a policy of selling a majority shareholding in some of its companies to black governments. This secures favourable treatment for Anglo — for example, when applying for permission to dismiss workers or raise prices — and gives the government an incentive to “look after” Anglo’s interests.

But real control stays in Anglo’s hands. Thus, at Hwange Colliery, Anglo kept the right to appoint the managing director and continued to run the mine. In his 1983 annual statement the new chairman reported:

“Mine and managerial arrangements together with administration and technical services have remained unchanged.”

Morgan Tsvangirai, ZCTU leader, describes the position in Zimbabwe today: “Who owns the means of production in this country? The white community. Let’s be factual. Whites may have lost the political power but they have the economic power, so they have different motives on investment.

“They milk you and blackmail you, bring you down to the level where they can control you economically and politically.”

It is clearly impossible to implement socialist policies on this basis.

Marxists explain that, as a first step, it is necessary to take key companies like Hwange Colliery into complete state ownership and establish workers’ management. This would make possible enormous improvements in working conditions and methods of production, and begin to create a basis for true economic planning. But it would not be the end of the struggle. The control of the imperialist monopolies over the world markets would continue. It is not only the capitalists’ ownership of the means of production that obstructs and distorts the development of Zimbabwe; it is the capitalist system as a whole that has the country in its grip.

To see what this means, let us look at the crises which have developed in Zimbabwe’s steel industry. Zisco and Lancashire Steel are both state-owned–yet both have remained at the mercy of the capitalist market.

Controlling what they don’t own

How can a multinational sell a company to the government and still keep control of it? Let us see what happens when the government buys shares.

A company’s “nominal capital” is divided into “shares” (certificates which entitle the owner to a proportion of profits, called “dividends”). Shareholders can vote at annual general meetings to elect directors and take decisions on company policy.

In theory, the shareholders who own a majority of shares should be able to run the company. In reality things are not so simple.

Even if the government “owns” Delta Corporation, for example, Anglo will have far greater influence over markets, supplies, management services, the transfer of skills and the investment of new capital. They have access to foreign markets; they can offer new investment; they can provide the technology which is needed for development.

These are precisely the things which every third-world government desperately needs. That is why a multinational company can have overwhelming power even if it owns a minority of shares. By threatening to withdraw, it can blackmail the government into accepting its demands.

That is why the government had to promise that the managers appointed by Anglo will continue to run Delta. The government, having paid Anglo millions of dollars in precious foreign exchange, had to stand back and let them continue to run the company as before!

Lancashire Steel

Lancashire Steel, producing steel rod and wire, used to be owned by the British Steel Corporation. In June 1984, heavily burdened by debt, it was taken over by the Industrial Development Corporation and Zisco, giving the government control.

Lancashire Steel, producing steel rod and wire, used to be owned by the British Steel Corporation. In June 1984, heavily burdened by debt, it was taken over by the Industrial Development Corporation and Zisco, giving the government control.

But state ownership did not solve Lancashire’s problems. The events that followed proved that the government’s policy was not socialist; it was only a pipeline for the wishes of the multinationals.

Under the Zimbabwe-South Africa preferential trade agreement Lancashire could export 1,000 tonnes of rod and wire to South Africa a month. This earned Zimbabwe about Z$5 million of foreign exchange per year.

But Lancashire’s sales were watched with envious eyes by Iscor and Haggie Rand (part of Anglo-American), the two giant concerns which dominate steel production in South Africa. Though capturing only two per cent of the SA market, Lancashire’s products were cheaper and better than theirs, and popular with small manufacturers.

That is why Iscor and Haggie were determined to squeeze Lancashire out of the SA market. The plan was to buy up Lancashire’s export quota; then they could resell it at a higher price, and so destroy its market.

In addition Haggie has a plant in Zimbabwe (just over the road from Lancashire in Kwekwe) which also makes wire and rod. So by destroying Lancashire’s market in SA Haggie would be better able to fight it for its Zimbabwean markets as well.

But Lancashire’s directors refused to sign their own redundancy notices. The government takeover of Lancashire gave the SA capitalists their chance.

A key role was played by Kurt Kuhn, managing director of Zisco under contract with the Austrian steelworks Voest-Alpine until the end of 1984. For Voest-Alpine their links with South Africa and Iscor were far more important than their involvement in Zimbabwe. So Kuhn took Haggie’s side in the battle against Lancashire, and seemed to have no trouble in persuading the government to follow his lead.

In particular transport minister Kumbirai Kangai (at that time industry minister) behaved like a servant of SA capitalism in his attacks on Lancashire Steel. Perhaps he was also taking revenge for the militancy shown by Lancashire Steel workers since Independence.

Thus the new directors appointed by the government immediately agreed to sell their export quota to Haggie — thereby placing the future of hundreds of Lancashire workers, and the survival of the plant, in the hands of the Haggie bosses down south.

Zisco

But Kurt Kuhn’s dirty work in helping to sabotage Lancashire Steel was nothing compared to the mismanagement that was exposed at Zisco itself.

In 1984 Chris Mapondera, a Zanu(PF) member, replaced Kuhn as managing director. In 1986 Mapondera was suspended and a commission of inquiry was set up to investigate his crimes. Its report, published in March 1987, exposed blatant corruption and incompetence at the top of Zimbabwe’s most important industry. As a result Mapondera and other directors were dismissed.

These events, the property-buying scandal on the railways and Willowgate confirm what every worker knows: a whole layer of the leadership — at the top of the state-owned industries, the party and the government itself — even while preaching “socialism”, are in fact slaves of the capitalist system.

Even the whites who headed the state-owned industries at the time of independence have been amazed at how quickly the new elite of black managers have attached themselves to the capitalist class. They have imitated the lifestyle of the colonial ruling class, preparing their sons and daughters for lucrative careers in business or in the civil service.

ZISCO: The workers were right

The Zisco workers had scented trouble from the start. During Kuhn’s long years at Zisco their jobs had seemed secure. Mapondera, on the other hand, had no qualifications for running a steel plant.

A qualified person to replace Kuhn had already been found — but then, mysteriously, Kangai “changed his mind” and insisted on appointing Mapondera. The whole transaction smelled of corruption, putting a question mark over the future of Zisco.

The workers’ instinct was correct. Kuhn had been lucky enough to end his contract just when Zisco was faced with serious crisis. Losses were mounting — from $64 million in 1983 to $82 million in 1986.

More and more government money was being poured into Zisco just to keep it going. By 1986-87, 96 per cent of the total industrial development budget was swallowed up by Zisco’s losses alone!

Plans had been made for a $200 million “refurbishment” (modernisation) of Zisco to make it more competitive on export markets. On the other hand Kuhn had started talking about “rationalisation” — i.e., job losses.

With Mapondera’s appointment workers feared the worst. They knew he had been a manager at Tobacco Auctions, and there had been dismissals. He had been a manager at Rio Tinto, and there had been dismissals.

A steelworker’s wife expressed the feeling of all the workers:

“If Mapondera is appointed, we will kill him.”

A socialist government would have given workers power to control the running of their workplace, including the appointment of all staff. But the government would not listen to the workers. Instead, Kangai himself came to Redcliif to try and enforce his decision.

The Chronicle reports what happened: “Redcliff’s Torwood Stadium was the scene of a rowdy three-hour meeting yesterday as more than 200 Zisco workers and their families shouted their disapproval… The workers insisted they did not want Cde Mapondera… They said that the appointment of Cde Mapondera was a result of nepotism… The crowd demanded an explanation of how Cde Mapondera rose to his position, but when he began to explain what he did after leaving school, they told him to sit down as this was history…” (2 October 1984)

In fact the workers’ anger was aimed not just at Mapondera but at Kangai as well. Kangai tried to manipulate the meeting by shouting slogans. “Down with imperialism!” he shouted. The workers answered: “Down with you!”

Some workers jostled Kangai, grabbing his arm and telling him what they thought. Two were arrested. As a woman later remarked: “When Kangai needed our vote he was good to us. But now that his stomach is big he forgets us.”

Twice that month the government discussed the Zisco crisis — not to consider the problem of management but the “unrest” among the workers. But the commission of inquiry proved that the workers had been correct.

It found that Mapondera had stolen many thousands of dollars from Zisco. He got free petrol for his company car at the rate of 1,100 litres per month. In Harare he ran up hotel bills of $16,365 in just 20 months — even though he owned a house there!

Workers’ control

Because the state-owned industries are run according to capitalist principles, these managers are under no democratic supervision by the workers. They are accountable only to fellow-officials, who have no interest in keeping a check on them.

Even when the government backed a “workers’ take-over” of Industrial Steel and Pipe in February 1989, it did so on the capitalists’ terms. $4.9 million was paid to the South African parent company which was disinvesting from Zimbabwe, and the previous management were asked to stay on and “help run the company”.

But, the workers soon found, according to the company’s constitution management could always over-rule them. “The company is being run by whites”, workers say, “and there is nothing that reflects that this is an employee-owned company.” (Sunday Mail, 25 June 1989)

A first step in combating this situation would be to make management accountable to their workforce. Every manager would have to be elected and could be dismissed by the workers if they lost confidence in him or her. The workers’ elected representatives would be involved in every aspect of management. Policy proposals would be put before mass meetings of the workers to be debated, approved, rejected or amended.

But vital as these measures are, they would not be enough to solve every problem. At Zisco, it is true, workers’ control would have made a quick end to “cde” Mapondera’s career. However, Mapondera’s corruption was only the tip of an iceberg — a symptom of more deep-rooted problems.

As Zisco chairman Divaris later admitted, the company was directionless and stagnating. It showed not only the consequences of mismanagement by a state bureaucracy, but, more fundamentally, the merciless pressures of capitalist “market forces” pushing Zisco into a dead end.

There was no progress with the refurbishment programme (see box Zisco: The workers were right). By September 1985 Mapondera put the cost at $312 million. He was kicked out soon afterwards — but even after he left nothing was done.

Delay meant colossal waste. By April 1987 the cost was estimated at $600 million. Another two years passed — and the government announced that $1,000 million (60 per cent of it in foreign currency) was now necessary for the job.

In May 1989, like old clothes which nobody wants, various parts of the rehabilitation programme were tabled at the London conference as “projects” for foreign investment!

Undoubtedly there is a crying need for Zisco’s products in Southern Africa. Yet, on the basis of capitalism, Zisco is caught in an impasse.

The Zimbabwean market, and even the SADCC markets, are too limited to justify investment in the latest steelmaking technology. Without this technology Zisco cannot compete with SA or European steel plants. Kurt Kuhn had warned that sections of Zisco were uneconomic and needed to be closed.

But, if this is done, more and more of the steel products required by Zimbabwean industry will have to be imported at a growing cost in foreign exchange.

On the other hand, to “refurbish” Zisco demands investment of over $1 billion, which Zimbabwe also cannot afford. That is why Zisco must look to the imperialist money-lenders.

But the capitalist system places limits on how far Zisco can expand. Full-scale refurbishment would mean a vast increase in its productive capacity. To make this pay for itself would mean finding new export markets — in other words, competing with the South African and overseas steel giants in a world market that is already oversupplied.

Either way the Zimbabwean government gets saddled with enormous debts. But, if Zisco sinks, it will mean perhaps 10,000 job losses in Redcliff, in the mines supplying Zisco and in other industries dependent on the steelworks. The government cannot contemplate a disaster of this scale — and so it continues pouring money into Zisco.

Whichever way this crisis is eventually dealt with, on a capitalist basis it can only be at the cost of Zimbabwe and the Zisco workers.

Socialists will always defend state ownership in place of private ownership as part of our overall programme of national and social liberation. But clearly the limited, piecemeal and bureaucratic extension of state ownership we have seen in Zimbabwe is not able to achieve the central economic aim of the liberation struggle — to gain democratic control over Zimbabwe’s resources and develop them for the benefit of the masses.

The government has poured huge resources into the pockets of the capitalists without developing new production. The economy has remained a colonial economy dominated by foreign imperialism and a local white capitalist class.

Market forces, manipulated by the giant monopolies, determine the income that state-owned companies are able to earn for their products and the prices they must pay for the equipment and materials they need. When competition sharpens, state-owned companies find themselves in a struggle for market shares with their mighty imperialist rivals.

Subsidies can keep state-owned companies from going bankrupt — but only at the cost of a growing drain on state resources and a mounting budget deficit.

That is why the government’s Transitional National Programme failed to achieve its targets, and why the present Five-Year Plan cannot succeed. These plans ignore the fact that the government has very little control over the economy. They are meaningless projections based on what the government would “like” the capitalist class to do.

But the capitalists, of course, are guided by their profit margins and not by the government’s wishes.

Further measures are clearly needed to bring the economy under democratic control by the working people so that we can direct our resources and reorganise production according to the needs of the masses. How can this be done?