PART III

THE TOOLS OF DIALECTICAL THOUGHT

Dialectical materialism is a method. It is not a master key that automatically gives us knowledge about the world. Dialectical materialism simply teaches us where to look for objective explanations. There is no shortcut around finding and studying the facts of all the things that we want to understand, including how things change. But how we organise and connect those facts in order to understand them is crucial.

Models, abstractions and generalisations

The use of models is one method to develop theories to connect and explain observations. In science a model is a way of describing how the world works. Models are simplified representations that allow us to understand something that maybe we can never even see – to develop a different ‘point of view’ than our five senses alone allow. The modern scientific model of the solar system allows us to understand far more than if we only relied on what we can see with the naked eye.

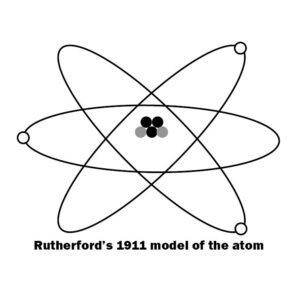

Some models ‘look’ nothing like the thing they describe. For example, atoms make up all matter in the universe, including us. The model of the atom pictured here was intentionally designed to ‘look’ like the solar system.

Some models ‘look’ nothing like the thing they describe. For example, atoms make up all matter in the universe, including us. The model of the atom pictured here was intentionally designed to ‘look’ like the solar system.

The model shows the three basic sub-atomic particles that make up an atom: a proton and neutron nucleus at the centre (the grey and the black circles) with ‘orbiting’ electrons (the white circles). The model represents these sub-atomic particles as small circles. But this model is a simplification of an atom to allow us to understand it. For example, electrons are negative electrical charges. Does a negative electrical charge look like a white circle? Almost certainly not. Protons and neutrons can be further broken down into ‘up quarks’ and ‘down quarks’. Do they really look like grey and black circles? Again, almost certainly not.

But nevertheless, leaving aside mathematical equations that allow an even more precise description of atoms, this model provides us with a representation of an atom that gives us an excellent understanding of the chemical elements and the interactions that create all the basic ‘stuff’ of the universe. Using this model we can make predictions that prove it describes important ways in which matter develops.

This model of the atom is an abstraction. What do we mean by an abstraction? We mean that we are literally removing something from its context in order to simplify it and understand it. This is a powerful tool of thought. Once developed a model can be generalised as we saw in Part I – i.e. applied to all similar phenomena. For example, we don’t need to examine all the trillions of atoms that make up a human body to check that they all fit this model of the atom. We use this model for all atoms until an observation suggests that it is not explaining something. Then we go back to ask ‘why?’ and develop a more accurate model from more precise observations.

Marxism uses this scientific method too. Marx’s epic work, Capital, is a detailed examination of how capitalist society works. It is a masterpiece in dialectical materialism. Marx examines the historical development of capitalism, but to describe the different economic processes within capitalism, he often simplifies them in simple abstract models, and even mathematical equations, before returning them to their historical context. Even basic ideas in Marxism make use of abstractions and generalisations, for example, the idea of “the working class”. At any given moment, in any given society, “the working class” is composed of different social layers and millions, now billions, of individuals. There are metalworkers, mineworkers, retail workers, office workers, unemployed, etc. Within every sector there is a division of labour and different jobs. There is no one individual who is a ‘perfect’ example of “the working class”. But it is an extremely useful generalisation that helps us understand society.

The limits of models, abstractions and generalisations

Many of the ideas and concepts that we use in everyday life are abstract and generalised models. These crucial ‘mental short-cuts’ stop us being overloaded with information. But these crucial ways of thinking have two sides to them. Understanding their limits is crucial to ensuring our ideas accurately describe the world. In everyday language people often point out that “it is wrong to generalise”. They usually, and correctly, mean that an entire group should not be condemned for the crimes of one individual. But in general philosophical terms it is only sometimes “wrong to generalise” but it is vital to know when. The point can be demonstrated with the simplest kind of model – a name, or label.

Look at this picture. What is it?

Did you answer “apple”?

And what is this?

Did you answer “apple” again?

We’re using exactly the same label to describe these two apples. Our label treats them as identical. But in fact they’re not identical. They are different shapes and different shades for a start! Now, if you knew that they were in fact different varieties of apple, instead of answering “apple” originally, you could have answered “granny smith apple” and “golden delicious apple”. But that doesn’t quite save us. Then I could have shown you these three “granny smith apples” below.

None of them is identical either. They are different shapes, sizes and shades. So whilst the label “granny smith apple” has narrowed things down it still treats very different things as identical.

None of them is identical either. They are different shapes, sizes and shades. So whilst the label “granny smith apple” has narrowed things down it still treats very different things as identical.

Day-to-day we can call these different varieties “apple” for convenience with no problem. But the label “apple” is too imprecise if we want to know which apple variety to use to brew a sweet cider or bake a good apple pie – not everything that can be described by the label “apple” can be used successfully!

Can more precise labels help us overcome this limitation? For example, can we give this apple…

…a completely unique label, for example, “apple 1”? The label “apple 1” applies to this apple and no other apple in the world. Every observable and measurable property of this apple that makes it different from all other apples – its size, shape, colour, weight etc. – is described by the label “apple 1”. Does this extreme narrowing down of the label allow it to accurately describe this apple?

…a completely unique label, for example, “apple 1”? The label “apple 1” applies to this apple and no other apple in the world. Every observable and measurable property of this apple that makes it different from all other apples – its size, shape, colour, weight etc. – is described by the label “apple 1”. Does this extreme narrowing down of the label allow it to accurately describe this apple?

The answer is: only for a fleeting moment. Because all of the features described by the label “apple 1” are undergoing change from one hour to the next and from one second to the next. This apple could only be described perfectly by the label “apple 1” if it did not exist in time. But everything exists in time. Any apple that has been picked from its tree is rotting. Within a shorter or longer period of time, the colour will darken and eventually turn brown. The firm round shape will become wrinkled, deformed and soft. All of the features that “apple 1” describes will no longer be present. Will it still be the same “apple 1”?

Yes and no. If we were to set up a time-lapse camera you could watch the apple rot before your eyes. But what we are left with is not “apple 1” but a “rotten apple”; the first we are happy to eat the second we would not even want to touch. The label “apple 1” becomes useless as describing this apple after just a few weeks because of the passage of time and processes of change.

Yes and no. If we were to set up a time-lapse camera you could watch the apple rot before your eyes. But what we are left with is not “apple 1” but a “rotten apple”; the first we are happy to eat the second we would not even want to touch. The label “apple 1” becomes useless as describing this apple after just a few weeks because of the passage of time and processes of change.

But if I hold on to the label “apple 1” I will have to insist that nothing has changed. If I do this I would be treating the label as more important than the thing it is meant to describe. The label becomes removed from its context and becomes entirely abstract. This leads to us treating the world as static and unchanging because our abstract models and labels are static and unchanging. This can take us straight back to the idealism described in Part II.

We are describing here the limitations of formal logic. Dialectical thought is sometimes called dialectical logic. Formal logic is not able to help us understand processes of change; dialectics is. The word ‘logic’ is still used today, usually in appeals to “think logically” about a problem or “apply logic” to the situation. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word ‘logos’, which means ‘reason’. It can help to think of different forms of logic as different methods of reasoning.

Abstract ideas about society

When trying to understand society, abstract labels that do not recognise processes of change have the same effect of confusing us. For example, we know what the ideas of ‘justice’ and ‘fairness’ mean in general but unless we place them in a context they are meaningless. The capitalist class’s idea of ‘justice’ is to receive a ‘fair’ profit from their investments; the working class’s idea of ‘justice’ is to have a ‘fair’ wage for their labour. But a high wage reduces profits; high profits reduce wages. The same labels of ‘justice’ and ‘fairness’ are used to describe different things. If you put a trade union wage negotiator and a factory owner on the TV news to debate each other they will throw the abstract ideas of ‘justice’ and ‘fairness’ at each other. Both will feel that ‘justice’ and ‘fairness’ is on their side from their own ‘point of view’ but they are guaranteed to fail to convince each other. So unless the debate moves beyond abstractions and defines ‘justice’ and ‘fairness’ by placing them into a context we might as well turn the TV off as we will not learn a thing.

Another example is the label “ANC”. This label has been used to describe an organisation that has existed for over 100 years. We use it as shorthand today to refer to this or that latest policy “of the ANC” or this or that latest case of corruption “of the ANC”. But when we are looking at the role of the ANC over the past 100 years, the label “ANC” is too imprecise to help us understand history.

For example, from its foundation in 1912 to the 1940s, the ANC was an elite lobby group, petitioning the British king, initially so that black people who owned property would be allowed to vote. In the 1950s and early 1960s with industrialisation, urbanisation and the development of the working class the ANC turned to mass actions such as boycotts and stay-aways. Through the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s the ANC was banned and existed mainly in exile. This gave it a more secretive and closed character whilst in SA itself the ANC was a symbol of the liberation struggle fought by other forces such as the students and the trade unions. After 1994 the ANC became the ruling party of a neo-colonial capitalist society. All of these phases of development of the ANC were very different to each other. So, which phase is described by “ANC”? Unless we are clear about which historical context we are using “ANC” to describe we will make mistakes.

One error that arises from the mis-application of the label “ANC” frustrates the youth in particular. For the youth “ANC” means “the ANC after 1994”, i.e. a neo-liberal capitalist government; for some of the older generation, particularly in the rural areas, the label “ANC” means “the ANC in the 1980s”, i.e. a symbol of the liberation struggle. The leaders of the ANC exploit this mistake in formal logic by the older generation to appeal for support for their anti-working class policies. But millions see through this trick when they say, “this is not our ANC”. This statement is actually a profound philosophical insight! It acknowledges change and the limits of the static label “ANC”.

Dialectical thinking

Trotsky summed-up how dialectical thinking helps us to overcome the limitations of static labels. He explained that:

Vulgar thought operates with such concepts as capitalism, morals, freedom, workers’ state, etc. as fixed abstractions, presuming that capitalism is equal to capitalism, morals are equal to morals, etc. Dialectical thinking analyzes all things and phenomena in their continuous change, while determining in the material conditions of those changes that critical limit beyond which “A” ceases to be “A”, a workers’ state[*] ceases to be a workers’ state.

The fundamental flaw of vulgar thought lies in the fact that it wishes to content itself with motionless imprints of a reality which consists of eternal motion. Dialectical thinking gives to concepts, by means of closer approximations, corrections, concretizations, a richness of content and flexibility; I would even say a succulence which to a certain extent brings them close to living phenomena. Not capitalism in general, but a given capitalism at a given stage of development. Not a workers’ state in general, but a given workers’ state in a backward country in an imperialist encirclement, etc.

Dialectical thinking is related to vulgar thinking in the same way that a motion picture is related to a still photograph. The motion picture does not outlaw the still photograph but combines a series of them according to the laws of motion. Dialectics does not deny the syllogism [the labels of formal logic], but teaches us to combine syllogisms in such a way as to bring our understanding closer to the eternally changing reality.

A Petty Bourgeois Opposition, 1939

[*The “workers’ state” Trotsky was referring to was Soviet Russia. In this polemic he was defending the Russian Revolution against those petty bourgeois (or middle class) ‘revolutionaries’ who, scared by the Stalinist degeneration of Soviet Russia had abandoned dialectical materialism and retreated into a form of idealism that attempted to blame “revolutionary doctrine for the mistakes and crimes of those who betrayed it”.]

As Trotsky explains, dialectical thinking does not replace the simple models so necessary for everyday life. Rather it connects them and places them on the spectrum of continuous development. Dialectical thinking means to train ourselves to remember that everything is constantly changing. This allows our thoughts and ideas ever “closer approximations”, or descriptions, of the world. By recognising change, the scissor-handles of human understanding are brought that much closer together.

The tools of dialectical thought (described below) are models. Like all models they are a simplified representation of the world that allows us to recognise and understand processes of change. Just as Rutherford’s model of the atom is not what an atom really ‘looks’ like, but a simplified representation, dialectical thought is not identical with the different processes of change but a general way of describing them. In that sense, dialectical thinking, like all models, is an abstraction. As Engels explained in Dialectics of Nature, “It is…from the history of nature and human society that the laws of dialectics are abstracted. For they are nothing but the most general laws of these two aspects of historical development, as well as thought itself.” Engels further explained that:

It is obvious that in describing any evolutionary process as the negation of the negation [one of the tools of dialectical thought explained below] I do not say anything concerning the particular process of development, for example, of the grain of barley from germination to the death of the fruit-bearing plant. For, as the integral calculus also is a negation of the negation, if I said anything of the sort I should only be making the nonsensical statement that the life-process of a barley plant was the integral calculus or for that matter that it was socialism.

Anti-Duhring, 1877

For example, the transformation of water through the states of ice-liquid-steam, and the development of European society through the stages of Ancient society-feudal society-capitalist society are both examples of change. But a change in the state of water is explained by the energy level of water molecules (thermodynamics); change in society is explained by class contradictions and the class struggle. But for us to recognise that what appear to be completely different things are actually different stages of development of the same thing we must think dialectically. This allows us to recognise that the different states of ice-liquid-steam are different arrangements of water molecules; the different forms of European class society are different arrangements of people into classes based on the level of development of the productive forces. The specific process of change must be discovered, as Trotsky said above, “in the material conditions of those changes”.

The word ‘dialectic’ comes from the Ancient Greek language and literally means “discussion”. But it is a discussion between people who may have different views to start with but want to work together to find the truth. A discussion recognises the possibility of change. In a discussion people can agree to meet each other half-way just as dialectics can describe how “apple 1” becomes “rotten apple”. So a discussion can be contrasted to a debate. In a debate people think that they alone know the truth. A debate is like the fixed labels of formal logic. There is no way for “apple 1” to become “rotten apple”. They don’t interact but stubbornly insist that they alone are correct.

The tools of dialectical thought

Marx and Engels put forward three ‘dialectical laws’ to describe processes of change. They used the word ‘law’ in its scientific sense which simply means a theory or an explanation for observations. But the everyday use of the word ‘law’ suggests a law-maker who first makes the law and then applies it to the world. This is of course the opposite of the way that we should understand ‘laws’ of dialectics. ‘Laws’ of dialectics are a description of the processes of development and change in the world.

To assist with clarifying this point, instead of talking about ‘laws of dialectics’ we can talk about tools of dialectical thought. In the hands of someone trained in their use, tools create useful products from raw material; dialectical thought can turn raw unconnected observations into a useful description of change. Marx and Engels’ put forward three tools of dialectical thought. They have old-fashioned philosophical names – they are (1) ‘the transformation of quantity into quality and vice versa’, (2) the ‘negation of the negation’, and (3) the ‘interpenetration of opposites’. But they can be made more memorable by giving them nicknames based on everyday phrases. Engels made the point that, “men thought dialectically long before they knew dialectics” so it is not a surprise that dialectical thought has found an unconscious expression in everyday language.

Tool 1: Change of Quantity into Quality

A.k.a. the straw that breaks the camel’s back

Within a limit an addition or subtraction does not change a thing. That limit depends on the process of change being considered. In the language of philosophy, certain changes in quantity do not affect the quality of a thing.

We already saw this idea in Part III when we considered the rotting apple. This was an example of a change in quantity leading to a change of quality. In the case of the apple the change in quantity is a subtraction as the apple rots away. The apple is still recognisable as an apple up to a certain point. But there will come a point where the apple has rotted so much that anyone coming across it could not say what it had started out as. The gradual changes in quantity (subtraction) produced a change in quality. From apple to detritus (decomposed organic matter).

An example of how the ‘change of quantity into quality’ tool can help understand change in society is the emergence of European capitalism from feudal society. In feudal society the role of money in the economy was limited. Most payments were ‘payments-in-kind’ not requiring money. For example, peasants provided labour in exchange for the landlord’s protection and access to his land. As the proto-capitalist merchant class expanded their trade within feudal society the sectors of the economy where exchange was regulated by money instead of payments-in-kind increased. Up to a certain point this expansion did not change the feudal character of society. However once a certain point – a certain quantity – was reached in the accumulation of wealth and power by the capitalist class they were compelled to struggle against the feudal ruling class which was holding them back. In England and France this led to civil war and revolution that put the capitalist class in power. These were the events where quantity changed into quality; capitalism was established as a new quality out of previous changes in quantity. As Marx said, “the new society developed in the womb of the old”.

Sudden leaps

A key idea of ‘the change of quantity into quality’ tool is the idea of a sudden ‘leap’ when the change in quality takes place. Just how ‘quick’ the leap is from a human point of view depends on the specific process of change. So boiling water ‘leaps’ from liquid to steam from our point of view when we see the first bubbles of steam. But ‘leaps’ in evolution are measured in millions of years. For example, the Cambrian explosion, when a rapid diversity of different animals evolved, took place over the course of 20-25 million years. In evolutionary time this is a ‘leap’ but from the point of view of a human life it is a million generations! So just like dialectics itself, the idea of a ‘qualitative leap’, is a useful abstraction but we have to place it in a context and apply it to a specific process of change to know what would count as a ‘leap’.

This idea is crucial when applied to society. It helps us to prepare ourselves for rapid changes in society and working class consciousness. This tool allows us to look for changing quantities to predict a later change in quality. Without it social change appears to come out of nowhere. For example, the 2011 Egyptian revolution overthrew the dictator Mubarak who had been in power for decades. Neighbouring Tunisia was going through a revolution but the spark that forced the Egyptian masses to draw the conclusion that they must follow was a rise in the price of bread. This was ‘the straw that broke the camel’s back’. To many, especially the capitalist media, this seemed to come from a clear blue sky. The day before the revolution began, commentators were no doubt saying how “things never change” and the “working class is too conservative”. But armed with ‘the change of quantity and quality’ tool revolutionaries can prepare for these sudden leaps and not be caught by surprise.

Tool 2: the negation of the negation

A.k.a. nothing lasts forever

In philosophical language, the term ‘negation’ just means ending or passing away. From that you can work-out that the ‘negation of the negation’ – the ending of the ending – is the idea that even something that causes one thing to end, will eventually end itself – nothing lasts forever.

Let’s consider the apple again. If left in an open field undisturbed, the pips (seeds) inside the apple will grow into a sapling (baby tree) consuming the apple as food. The apple will be negated by the sapling. But the apple tree that will grow from the sapling will not last forever. It too will be negated, dying at a certain point.

But ‘the negation of the negation’ does not say that things repeat in an endless cycle. Through each ‘negation’ development takes place. In the example of the apple the gradual process of natural selection (an evolutionary process of change in nature) will take place. Only those pips that are best able to grow in the climate that year (it may be wetter than average or there may be a drought) will survive. They will pass on that slight advantage to the next generation and the apple tree as a species will change.

Let’s use another example from society. In primitive societies land was owned in common (or not owned at all). This was negated by the development of class society which introduced private ownership of land. Marxists anticipate that private ownership will in turn be negated by common ownership. But it will not be the common ownership of primitive societies but socialist common ownership based on a highly developed economy.

Tool 3: the interpenetration of opposites

A.k.a. life is never simple

The world is full of opposing forces. In philosophical language we would say that the world is full of contradictions. But opposing forces always exist together. For example, the north pole of a magnet attracts the south pole of another magnet. But every magnet has both a north and south pole. If you cut the magnet up it always has a north and south pole. These opposites exist together – they ‘interpenetrate’.

Let’s examine the apple. The chemical bonds that hold its atoms together are being opposed by chemical processes causing those bonds to break leading to the rotting of the apple. The forces are in opposition to each other. They contradict each other but are contained within the same object.

In society this presence of contradiction can be seen in the class struggle in capitalist society. There is the contradiction between the interests of the capitalist class to make profits and the working class to receive higher wages; the contradiction between the capitalist class’s individual (or private) ownership of the economy and the collective work of the working class.

The inter-connection of the tools

Each tool of dialectical though has its own ‘specialised’ use but they are all interrelated. In other words, to produce a useful product you almost always have to use all three together. You cannot build a piece of furniture with a hammer alone! Tool 3 ultimately connects the other two and can lead us back to them. For example, the accumulation of contradictions at one pole can eventually outweigh the other pole and these changes in quantity lead to a change in quality (Tool 1) negating (Tool 2) the thing we started out with.